LLVM Dev. Meeting 2023 Trip Report

From October 10th to 12th, 2023, I attended the LLVM Developers Meeting 2023, where I also participated in a co-located workshop on MLIR. This was my second time at this conference. I managed to take some notes, which I want to share with you in this blog post. I hope you find them helpful, too. Disclaimer: I was mainly interested in talks related to MLIR targeting general-purpose languages, program analysis, and interpretation. You won’t find a comprehensive trip report here. Additionally, I touch upon several security-related topics for my colleagues at Trail of Bits. Luckily this year’s program was a bit less MLIR-focused, which actually made it easier to decide on a single track to follow.

For those who may not be familiar, MLIR is a toolkit designed to help build custom Intermediate Representations (IRs). It’s a versatile platform that allows developers to create abstractions tailored to specific needs, facilitating more efficient optimization and analysis of code. While it originally found its niche in machine learning and linear algebra optimization, the “ML” in MLIR stands for “Multi-Level,” not “Machine Learning.” This distinction is essential because MLIR has since evolved to accommodate a broader range of general-purpose programming languages, making it a pivotal player in the future of compiler technology. The witness is our work on MLIR-based frontend for C/C++ called VAST, but also many others like ClangIR, Flang, or JSIR for Javascript. I recommend that everyone catch up with Alex Zinenko’s presentation on general MLIR misconceptions when it becomes available.

MLIR Workshop

On the first day of the conference, I attended the MLIR workshop. Throughout the workshop and the rest of the conference, the discussions revolved around various aspects of MLIR’s design, particularly concerning interpreters and the description of MLIR semantics. Several speakers offered their insights on the topic, and these discussions can be summarized in four key directions:

-

Semantic by Transformation: The semantics of operations is defined by their transformations, often into executable target LLVM or other target representations. This implies a single operation can have different semantics based on the target platform or user-defined conversions.

-

Semantic by Translation to Dialect: Semantics of operations is defined by translating them into a semantic dialect, typically a formal description of computation (e.g., SMT). Semantic dialects have precisely defined semantics, in contrast to target-specific conversions.

-

Semantic by Interpretation: By offering an interpreter for your dialect (e.g., Mojo implements an interpreter using interfaces attached to operations), you implicitly establish the semantics of operations.

-

Semantic by Operation Folding: Semantic can also be defined through operations folding, as they perform compile-time interpretation.

There’s also a somewhat vague semantic provided by the specifications and documentation of dialects, but adherence to this contract is not always mandatory. The community’s concern is that these semantics can diverge, potentially leading to translation, folding, and interpretation variations. In a comprehensive definition, the result should be consistent whether you perform constant folding on an expression in the MLIR dialect, translate it to LLVM and evaluate it, or interpret it.

MLIR Advancements

When it comes to the design of general-purpose languages, I was particularly intrigued by talks that explored general advancements in MLIR. These talks focused on introducing a bytecode format and modernising MLIR’s types and attributes by assigning names to them.

Currently, types and attributes, unlike operations, lack explicit names (although their textual form may suggest otherwise). This deficiency necessitates dialects to manage printing and parsing, leading to complexities in IR pattern matching and the need for more verbose naming. There’s a proposal in the works to rectify this by adding names (stay tuned for the RFC).

Starting with LLVM 17, MLIR introduced improved support for its bytecode format, offering a standardised and compact representation of MLIR. This bytecode format delivers enhanced performance and features compared to the textual format. Dialects can opt-in to provide versioning and support for backward and forward compatibility changes and deprecation. Additionally, it facilitates mechanisms for bytecode auto-upgrades. Notably, bytecode’s lazy loading feature materializes options as needed, which can be particularly helpful for processing large MLIR files.

However, the current design has drawbacks, as upstream dialects are not versioned, making them unusable with versioned user-defined dialects. Hopefully, this will change as dialects mature.

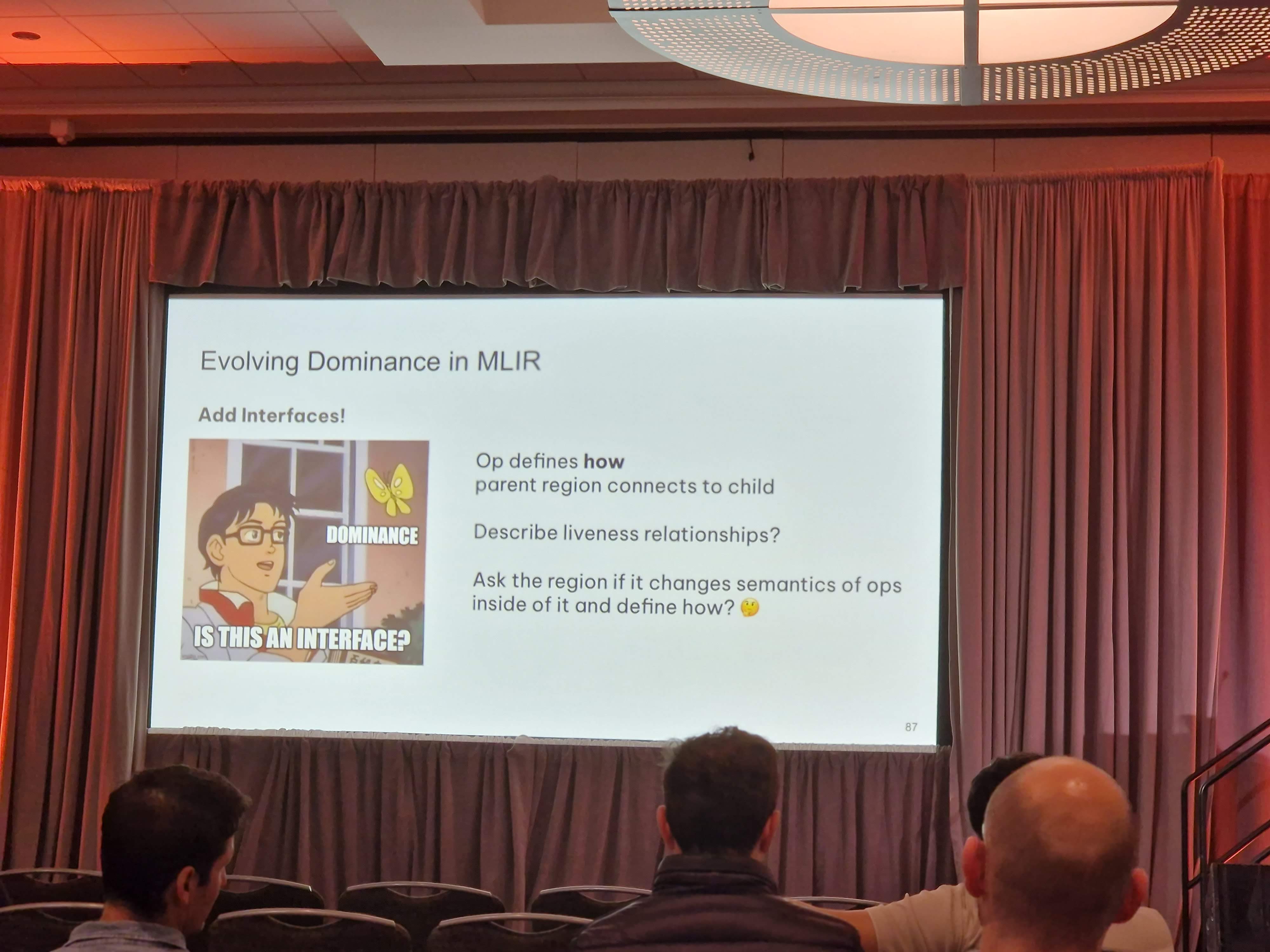

Dominance in MLIR

Another talk that focused on general MLIR was on correctly extending dominance to mlir regions. This was particularly interesting, as dominance is one of the problems we need to tackle in VAST as well to perform analysis on MLIR (it gives information on reachability and liveness).

The core concept of the presentation revolved around the notion of extending LLVM dominance to MLIR. In LLVM, one node X is said to dominate another node Y if all paths from the entry point to Y pass through X. In contrast to LLVM IR, MLIR provides a new concept of regions that serve as a more versatile form of scopes. These regions can encompass basic blocks, which, in turn, house operations, and operations can even contain multiple regions, creating a complex hierarchy. Applying LLVM dominance directly to regions in MLIR is intricate due to the various control-flow semantics associated with the operations they are attached to. For instance, operations stemming from a region of an async operation don’t directly dominate subsequent operations because they don’t technically precede them in the conventional sense.

The proposed solution presented in the talk aligns with the common approach in MLIR to any problem – add an interface that describes the region’s interaction with the dominance. It’s worth noting that this work is still a work in progress, and the authors welcomed any new ideas and contributions to further advance their solution.

MLIR Interpretation

Multiple talks centered around the topic of MLIR interpretation. A similar approach was adopted by both the xdsl and Mojo projects, which involved specifying interpretation interfaces for operations. This approach provides users with a valuable customization point for their dialects, allowing them to integrate into a general interpreter. In essence, the InterpreterOpInterface mandates that the operation implements the interpret function, which accesses and modifies the interpreter’s state.

The MLIR interpreter opens the door to a variety of exciting possibilities. As previously mentioned, it is equivalent to constant folding, making it a versatile tool for tasks like metaprogramming and validation. For instance, it can help ensure that intermediate IRs produce the desired results, allowing us to bisect passes when results diverge from expectations. One can also partially interpret MLIR and subsequently dump the interpreter state to the IR for runtime utilization.

While MLIR’s ambition to be versatile and adaptable to diverse use cases is commendable, it poses challenges for interpretation in accommodating all dialects’ unique requirements. A notable example is the complexity that arises when assigning control-flow semantics to blocks and regions, as different dialects attribute them with varying meanings.

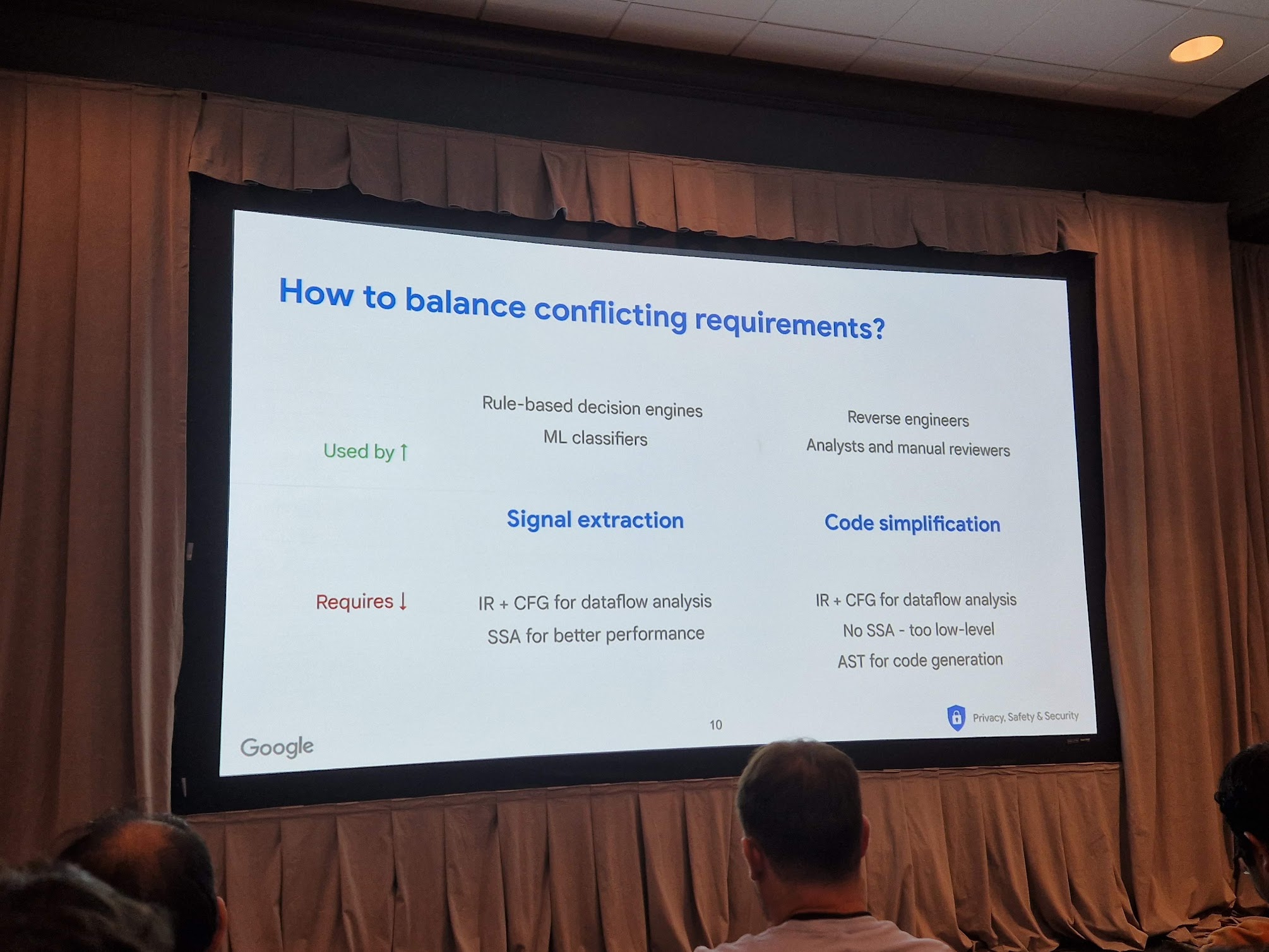

JSIR: Adversarial JavaScript Detection

Another talk that caught my eye was ‘Adversarial JavaScript Detection.’ This presentation by Google’s security team delved into JavaScript analysis using MLIR, primarily focusing on deobfuscation, and taint analysis for steganography.

The highlight of the talk was the introduction of a reversible JavaScript IR (JSIR) – soon to be open-sourced. This approach allowed them to generate MLIR from JavaScript source code and then lift it back to an AST to regenerate the source code. This process enabled them to simplify the code on the MLIR level, making it more accessible for manipulation and analysis.

What’s particularly intriguing is the JSIR’s ability to map back to the AST, similar to the high-level dialect in VAST. This thoughtful design balances meeting user analysis requirements and providing user-friendly and analysis-friendly representations:

One interesting low-level design problem was how to map block-based control-flow structures (CFG) back to the AST. JSIR accomplished this by introducing no-op operations, such as jslif.if, jslir.if_true, and jslir.if_end, to provide annotations for how blocks are connected to high-level control flow.

CIRCT

While CIRCT is primarily aimed at circuits, it faces similar challenges as general-purpose languages. This year’s talks highlighted the progress made in CIRCT over the past year. Two specific issues caught my attention as they resonate with the design challenges we encounter in VAST when dealing with C/C++: MLIR lacks adequate support for high-level symbols and typedef-like operations. In contrast to MLIR’s provided SymbolTable, CIRCT offers its custom SymbolTable, which allows referencing constructs that are not immediate children of the SymbolTable, including block arguments and elements of aggregate types. For more details on the design discussions related to typedefs, you can also watch the discussion from MLIR’s open meeting “Typedef” in MLIR. Similar issues arose in the VAST, ClangIR, or JSIR, and it would be great for MLIR to adapt more general SymbolTable to become a better representation for high-level IRs.

LTL & SMT Dialect

From the program analysis perspective, interesting extensions were presented as dialects for MLIR, including the standalone SMT dialect and the LTL dialect, which is a part of CIRCT. These dialects enable the uniform representation of program properties and, furthermore, permit MLIR dialects to directly express translations to these representations. This capability facilitates the verification of the correctness of program transformations. We can perform a translation of the program both before and after the transformation into the SMT dialect. Subsequently, we can inquire with the SMT solver about the semantic equivalence between the translated program and its original form. Moreover, I envision additional applications, such as integrating these translations with symbolic execution or employing these dialects to describe invariants within the program.

Mojo & ClangIR

The highlight moments for me were two presentations: the keynote on the Mojo 🔥 language and the advancements in ClangIR – MLIR dialect for C/C++. Both provided in-depth technical insights into their respective languages. Mojo, as a Python superset, is poised to shape the future of AI development, boasting a remarkable 44,000x speed improvement over-interpreted Python. What intrigued me most was the design choice to tightly couple the IR with the language, allowing for extensive opportunities for reflection and compile-time programming.

I was delighted to observe the growing interest in ClangIR, an MLIR dialect similar to VAST’s. It aligns with our focus on high-level optimization and analysis in C/C++ compiler design. Notably, both projects gradually encompass more significant portions of the C/C++ languages. For those interested, you can experiment with ClangIR on Compiler Explorer, and the VAST version will soon be available, too.

Enhancing C++ Security: Libc++ Hardening and Buffer Overflow Warnings

In the pursuit of making C++ more secure, two intriguing talks highlighted significant improvements. One focused on hardening Libc++ to address undefined behavior (UB) proposed in RFC, while the other introduced new Clang compiler warnings for detecting and mitigating buffer overflows with associated automatic code improvements proposed in RFC.

Libc++ Hardening

The primary objective of this work is to address UB in Libc++ by translating selected UB instances into traps. These traps provide a robust mechanism for detecting and handling security-critical issues. To cater to different use cases and performance requirements, users can choose the hardening level of the library at compilation using the -flibc++-hardening=<mode> flag.

The available hardening modes are:

- none: Is default mode that does not compromise any performance.

- fast: This mode focuses on security-critical low-overhead checks only (validity of input range and element access checks).

- extensive: In this mode, additional low-overhead checks are included, e.g., non-null arguments, non-overlapping ranges, and checks on compatibility of allocators.

- debug: This mode activates all checks, covering further internal checks.

Please note that some checks may require an ABI break, such as having a different representation of an iterator for overlap checks of spans. In such cases, it is left to the library vendors to determine the mode they provide on their system. This approach ensures that users are not burdened with ABI-related concerns, as the ABI is a property of the entire platform.

Unsafe Buffer Usage Warnings

The related talk on buffer overflows introduced a new option for the Clang compiler to check for unsafe buffer usage and provide valuable suggestions for code improvement. Static analysis for these options leverages the work done in the hardened Libc++ library and provides a mechanism to migrate codebase to hardened stdlib types.

To use this feature, compile your C++ code as follows:

clang++ -std=c++20 -flibc++-hardening=fast \

-Wunsafe-buffer-usage -fsafe-buffer-usage-suggestions \

source.cpp

Here’s a practical example: think of a piece of code that’s using a basic C array like int buf[32]. Using the newly available option, clang spots this kind of usage and recommends replacing it with the hardened std::array. Additionally, the automatic tool also handles pointer-arithmetic transformations into access operators. Further it recommends the use of std::span in situations where raw pointers are used as buffer views.

I’ll conclude by emphasizing that the LLVM community continues to evolve and grow. While it has transitioned to GitHub-based contributions, it faces challenges in governance. One notable talk highlighted these issues, proposing the adoption of a community technical governance model to ensure the community’s long-term health – see A Proposal for Technical Governance (RFC).